Describing Chamonix as “contagious” is probably not a great choice of words at the present time, but it’s true that the valley has been captivating its visitors for several centuries, to the extent that many keep returning, both winter and summer, and some just never leave!

Is it the characterful town that draw visitors back, or the mountains with their cascading glaciers, or the people that so readily share their passion with others?

The pandemic has of course made travel more difficult, but the good news is that Chamonix will always be there.

For those who do not know the destination already, Chamonix Mont-Blanc is both a town and a 28km-long valley. Along the valley floor lie a number of traditional villages and hamlets, each with their own personality and each staking a claim on the majestic summits and their eternal snows above.

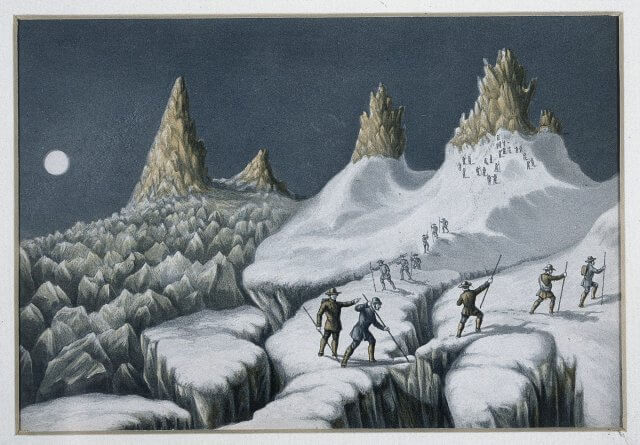

People have been coming here far longer than most other ski destinations, and indeed since long before downhill skiing was thought up. In 1741, the first official visitors to the Chamonix Valley were two Englishmen, William Wyndham and Richard Pocock. Their legacy to the valley was the “Mer de Glace” (sea of ice), the name they bestowed on the impressive Montenvers glacier.

20 years later, another illustrious visitor said of the valley:

“These majestic glaciers, separated by great forests and crowned by granite crags of astounding height cut in the form of huge obelisks mixed with snow and ice, present one of the noblest and most singular spectacles it is possible to imagine.”

Not a lot has changed in the more than two-and-a-half centuries since.

Following the conquest of Mont Blanc in 1786, explorers, mountaineers, tourists, artists and scientists were drawn inexorably to Chamonix. The dry Scot, James W Forbes, considered to be the precursor of glaciology in the early 1800s, spent many years studying the movement of ice. He developed lifelong friendships with local guides, alongside a passion for the Mer de Glace, and was rather derisory of anyone who didn’t fall in love with Chamonix.

“He who does not feel his step lighter and his breath freer on the Montanvert and the Wengern Alp, may be classed among the incapables and permitted to retire in peace to paddle his skiff on the Lake of Geneva or to loiter in the salons of Baden Baden,” he said.

It was John Ruskin, the 19th century artist and poet who coined the phrase “mountains are the great cathedrals of the earth”. At the foot of the Brevent, the Ruskin Stone bears witness to the hours he spent in tender contemplation of nature: “I never saw the valley look so lovely as it did tonight! With its noble, quiet slopes of deep, deep green and grey, and, above them, the rich orange of the Aiguilles. I know nowhere else where one sees green and orange united by purple, as the sun leaves the pines and remains on the granite. The great waterfall across the valley was bounding with ever wilder crashes … and the wind brought its roar to me across the fields. The sweet level fields!”

Many more colourful quotes testify to the Briton’s love affair with Chamonix, but this is a favourite. After successfully climbing Mont Blanc in 1851, the impresario Albert Smith wrote in his diary:

“the peaks looked like islands rising from a filmy ocean – an archipelago of gold; the sight was more than the realisation of the most gorgeous visions that opium or hasheesh could evoke.”

©musée alpin

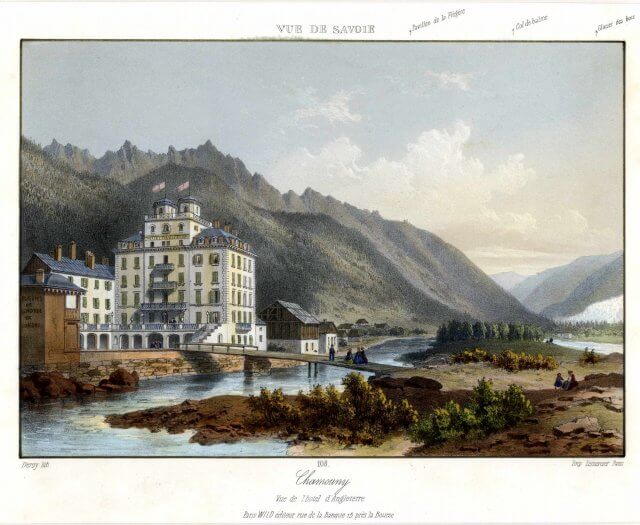

Grand hotels sprang up in the late 1800s, bearing the names of Hotel de Londres, Hotel d’Angleterre, Hotel Royal, Hotel International… The small farming village was growing into a cosmopolitan destination and the arrival of the train in 1901 confirmed the prosperity of the Belle Époque.

The passage into the 20th century was hailed by the arrival of long wooden planks that were to gaily revolutionise the interminable winter seasons in Chamonix. In 1898, at the age of 10, the Englishman Arnold Lunn tested his first pair of skis on the valley’s slopes.

While he was not particularly enthused at the time, he went on to become a key player in the development of alpine skiing. In 1924 the first Winter Olympic Games took place in Chamonix, but due to Scandinavian opposition, downhill skiing was not on the agenda! Lunn consequently organised the first international competition, the Arlberg-Kandahar, in 1928, and the rest is history…

During the “Années Folles” in Chamonix, three splendid hotel palaces, with magnificent gardens and ballrooms, attracted aristocrats and dignitaries from the world over. One of these superb buildings, the “Majestic” is Chamonix’s Congress centre, the second is proudly occupied by the Alpine Museum and the third, the Savoy Palace, recently reopened under the patronage of the Folie Douce hotels. The bygone era of crazy partying has been revived, and the British are still there having fun!

©musée

For well over 250 years, the British have kept a special place in their hearts for Chamonix. Many, like Victor Saunders, president of the Alpine Club, mountaineer, guide and author, have chosen to make the valley their home. The passion that Chamonix dwellers share for this extraordinary environment is what brings them together, whatever their nationality.

The challenge of the 21st century is how to protect this heritage, how to continue to enjoy the Chamonix Valley without compromising the lives of those who will become the future guardians of this temple of nature.

To quote the voice of reason of the English alpinist and illustrator Edward Whymper, author of ‘Scrambles amongst the Alps”, a loyal visitor to Chamonix from 1860 to 1911, who now dwells in Chamonix’s cemetery:

“Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are nought without prudence … do nothing in haste, look well to each step and from the beginning, think well what may be the end.”

If Alpinism is a metaphor for life, then the pioneering spirit of mountain-lovers will doubtless meet the challenges of the future.