We first interviewed the world’s most travelled ski adventurer and self-declared ‘ski bum’ Jimmy Petterson in 2015. Five year’s on he’s skied still more resorts around the world and we think more countries than anyone else, he also has probably the biggest ski book ever published out, volume two of his Skiing Around The World epic.

Jimmy Petterson has devoted most of his life to skiing, with about 4600 days under his belt, and still counting. For years, he has shared his experiences in ski magazines all over the world. He has produced more than 600 feature articles and 30 front-cover shots, and his work has been published in 20 countries.

In 2005, he first published Skiing Around the World, and now, after 14 years in the making, he has published Volume II of Skiing Around the World and reprinted Volume I, which has long been sold out. By now, he has skied in 75 countries on all seven continents, and they are all included in his two-volume set.

ITS> You have a fascinating background, Jimmy. Academically, you prepared to be a teacher, but then you pivoted and began a series of adventures that has taken you skiing on all seven continents. In a way, by becoming an author and sharing your adventures in books, magazines, and television shows, you never really strayed that far from teaching. You just did it on your own terms. When did you realize that classroom teaching wasn’t going to be fulfilling?

Jimmy: That is a very good question. After graduating from university, I decided to spend a season in the Alps before getting down to “real life.” I managed to get a job instructing skiing in the Austrian village of Hinterglemm. To paraphrase Mark Knopfler, it was not exactly “Money for nothing and the chicks for free,” but it was “Almost no money, but the chick were definitely free,” and there were plenty of them. After the ski season ended, my address book was full of girls’ names that I spent a good part of the summer visiting all over Europe. By the time the summer was over, I decided to merely work the autumn as a substitute teacher and do another season in Hinterglemm. Partway through that season, a local travel agent saw me playing guitar and singing in a local après-ski location with a group of other instructors. He offered me a one-off job to entertain his Scandinavian guests for an evening. Ahh-ha—the light bulb experience. I could earn more money singing in the evenings, abandon the beginner’s hill, have days free to ski powder, and as an entertainer, “the chicks were still for free.” I couldn’t resist. This led to a few more seasons earning my way by singing rather than instructing, and continuing to work as a substitute in the fall.

Before I knew it, I was five years older, and had still not really made an attempt at my chosen profession as a history teacher. So, for the school year of 1978-79, I did not return to the Alps, but taught history at a high school in LA City Schools. While it was a good experience, it was not easy. The school had a mixed makeup of middle and lower class students, a majority of whom were minorities. All were basically nice kids, but many—even in 11th grade, were functional illiterates—having been passed on from grade to grade by a failed school system. By the time they had reached this stage, they were not motivated and just putting in their time, hoping to ultimately get a high-school diploma. There were too many kids in each class—sometimes more than 40, if they all attended. I worked hard and still feel good about that year, but it was certainly culture shock to adjust from teaching and singing for groups on international skiers to trying to knock some sense into the heads of disinterested 17- and 18-year-olds in L.A. After that experience, I knew that the lifestyle in the Alps, with all of its side benefits, suited me better, and I never really looked back after that. I did continue to work as a substitute teacher every fall for LA City Schools until the mid-1980s, but never seriously considered going back to full-time teaching.

I got my BA in history and my MA in “Instruction and Curriculum”. In a way, one could say that both of those studies prepared me for what I ended up doing. In my writings, while the main topic is skiing, I invariably include some history of the country or area that I am describing. Working on my MA, we had courses in how to create content for our students—written content, slide shows, etc. In the end, that also served me well, when I ended up creating ski content.

ITS> As a “self-described” ski bum of 40 years, you’ve undoubtedly experienced a lot of adventures on and off the slopes. What are some of the most unique jobs you’ve taken on to support your on-slope adventures?

Jimmy> I have had lots of jobs, but very lucky to have supported myself for many years with the rather glamorous occupations of ski journalism, photography, and entertaining with song and guitar. However, over the years, I have also ski instructed, owned a bar, leased a small pension, done coat-check in a disco, taken care of the entry fee at a club, worked as a travel guide, and organized corporate ski trips. I still organize corporate ski travel today.

ITS> What was the very first ski resort you visited?

Jimmy> My earliest ski experiences were in the small ski areas of Southern California, where I grew up. They include Mt. Baldy, Snow Summit, Snow Valley, Kratka Ridge, Table Mountain, Mt, Waterman, Holiday Hill, and Blue Ridge. Some of these are now defunct, and Holiday Hill and Blue Ridge long ago combined to create Mountain High.

ITS> You’ve skied in 75 countries. If you could only ski in one country for the rest of your life, which country would you pick? Since you’re an ex-pat currently living in Austria, I’m guessing you have an affinity for the Alps?

Jimmy> It is not easy to pick just one country. I do prefer the Alps to the skiing in the US. The ski areas are larger, the atmosphere is more fun and more authentic, the après-ski and nightlife is much better, the cost is probably less than half, the piste-preparation is much better, and the clientele is very international, which is fun, too.

Erik Petterson Sjöqvist gazes down the jaws of the Val di Mezdi, situated in the Dolomites, one of the most beautiful descents in the world.

I love skiing in Austria, where I now have residency. But the Italian Alps are also wonderful. The Dolomites are perhaps the most beautiful range of mountains in the world, and of course, the Italian food, wine, and ambiance, is also special. I also love skiing in Norway. My father’s homeland is perhaps the most beautiful country I have visited, and there are numerous ski areas, like Narvik and Stranda, where you can ski with stupendous views of the fjords.

I also enjoy Baquiera-Beret in the Spanish Pyrenees. And for unique experiences, there are other locations that have been very special to me. Iran has great powder and the people are among the most kind and hospitable in the world. Gulmarg, India is blessed with great off-piste skiing, spectacular scenery, and a very interesting and exotic culture. And the small volcano ski areas of southern Chile again have wonderful scenery and a low-key, back-to-the-roots ski experience.

ITS> Any idea how many separate ski areas you’ve been to? Is there one ski area that has been particularly memorable?

Jimmy> I have skied in 649 ski resorts.

The unusual train built by NATO that nowadays takes skiers to the top of Gaustatoppen (see below).

ITS> What has been the most unique ski area you’ve been to?

Jimmy> There are a number of unique places. What immediately comes to mind is Gaustatoppen in Norway. It is the highest mountain in that part of Norway, and they say you can see 1/6 of the country from there. In the 1950s, the US paid for building a strange small train in two stages that is tunnelled through the mountain. The purpose was to build a NATO station on the peak to do radio-spying on the Russians. In recent years, the Norwegians decided to open this mountain for freeride skiing. There are no pistes. The same odd train built for NATO today provides access for skiers.

This tow, in Broken River, is one of the nefarious rope tows of New Zealand. It took Jimmy ten tries to successfully ride up the first time he says.

The rope tows used in many of the New Zealand club fields are also legendary. Rope tows, which were a common early form of ski transport, are now mostly used on beginner hills in many resorts. New Zealand is different. They have very fast moving rope tows that take skiers and boarders up more than 500 vertical meters of difficult terrain. To ride these terrifying contraptions, you must first buy a special glove to protect your ski glove. Otherwise, the speed of the rope will burn a hole in your glove. Then, when purchasing a day pass, instead of a ticket, you are loaned a nutcracker. This is a 5-inch wide belt to attach around your waist. From the belt hangs a nutcracker shaped device—a metal chain with the nutcracker hanging on the end. To ride this swiftly moving rope, you must grab hold with your right hand, covered by the extra glove, and then, within three seconds, negotiate a dexterous flip motion to get the nutcracker to wrap around the rope. Then quickly release your right hand and squeeze hard with both hands on the nutcracker so that it clamps down around the rope, so that it pulls you up the mountain. Why must you release your right hand within three seconds? Because after three seconds, the rope goes through a sharp, metal pulley wheel, and if your hand is still on the rope at that time, you will no longer have a hand!

There are many more unusual and unique lifts and experiences in the ski world, but I must refer you to my books for more information.

ITS> What was your best ski day, and your worst ski day?

Jimmy> When one has skied about 4500 ski days, it is not easy to single out the most memorable, but attempting to name just one, I think back to March 10, 1980 in St. Anton. It had snowed for days with total whiteout conditions and virtually impossible to ski with no visibility. March 10 appeared to be the same, as a peek out one’s bedroom window at 8 a.m. was a picture of milky white. I, however, had an inkling that this time, it was mere ground fog, and that the storm had abated. I was right. Halfway up the mountain the gondola broke through the fog to sunshine. Most of the ski bums, and other skiers, however, stayed in bed. I experienced more than 10,000 vertical meters of the lightest, waist-deep powder, and there was nary a soul on the mountain.

Jimmy Petterson enjoying epic conditions on March 10, 1980, on the Rendl, in St. Anton. Photo by Iggy Holm.

To name a worst ski day is equally difficult. There have been many bad days. Some are just bad because it is icy and grey or slushy and raining. They blend with one another and are not worth mentioning. Worse still are brushes with death as a result of avalanches and injuries. Probably my worst day was skiing with Phil Mahre on his home mountain at White Pass, Washington. He is a nice man, and it was fun at first to ski with this ski legend despite poor conditions because of a full night of rain the previous night. But at midday, I hit a particularly soft patch of snow while skiing at high speed and both heels released. The result was a broken neck (pictured below).

Jimmy Petterson, on a less than epic day in White Pass, Washington. Photo by Ortwin Eckert.

ITS> Your trips have taken you to areas such as Kazakhstan, China, and Soviet Georgia. Are there some areas that were particularly challenging to visit?

Jimmy> One would think that North Korea would have been most challenging—particularly because of all the negative press it gets in the West, but it was certainly easier and less complicated to get a visa to that country than to visit the US.

China was difficult to organize. I had to deal on the phone and over the Internet with a number of Chinese travel agencies, send them a lot of money, and hope that they were honest, and that there really would be somebody to meet me at this train station or that airport. In the end, it all worked out fine.

In Iran, also because of bad press in the West, I was uncertain whether I should tell people, who invariably asked, that I was American, or say that I was Swedish or Austrian, the two countries, where I have homes. Ultimately, I decided, with some trepidation, to be honest, and say I was American. That was always greeted with a positive response . . . “I have relatives in Cleveland” . . . or “Oh, I like America. You are lucky to be from there.” I met nothing but wonderful hospitality in Iran. While I have found people to be kind almost everywhere, Iran has stood out as the most friendly people I have experienced among the 95 countries that I have visited.

Tajikistan was also challenging, as there is almost no tourism and very poor infrastructure. Believe it or not, the trip was finally beautifully organized with the help of three NGO workers—an Austrian man, a French woman, and a Russian man, all of whom I connected with through a blog about ski-touring in Tajikistan. In the end, after many emails, they said, “Don’t worry about a thing. Fly here, and we will organize everything.” That saved me a lot of money of going through a travel agency, and it worked perfectly. They organized hotels, an itinerary, stays with a family in a primitive mountain village, a driver with an SUV to chauffeur us from place to place, and they guided us on skis as well.

The moral of the story is: Whenever you can, do it organically.

ITS> Are there any off-the-beaten-track ski areas that we should consider adding to our wish list?

Jimmy> There are many—too many to mention all. For that, you really need to go through both of my books, Skiing Around the World Volume I and II. Try skiing in any or many of the 20 ski resorts in Greece. Kalavryta, when I was there three years ago offered a three-star hotel with breakfast AND a lift pass for $35 a night!!! Small ski area, but empty slopes and very good skiing. Mt. Erciyes in Turkey is an extinct volcano. Not only is the skiing good, but also the surrounding scenery of Cappadocia (below) is one of the wonders of the world. Make sure to do a hot-air balloon trip here. I include a photo. There are small, unknown ski resorts all over the Alps that are often better and more authentic than the more famous resorts. I love Val d’Anniviers in Switzerland.

The magic fairy chimneys of Cappadocia are a short drive from the ski resort on Mt. Erciyes.

ITS> As an avid skier across multiple decades, you’ve witnessed a lot of changes in the industry. What is one positive change you’ve observed, and one negative change?

Jimmy> Another excellent question. The biggest change—and very positive—is ski grooming. In my early years of skiing in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the first day after a snowfall, some small moguls appeared. These continued to grow until the next snowfall, and if a lot of time passed, you ended up with bunker-sized moguls everywhere. In spring, they would be solid ice in the morning and heavy sorbet in the afternoon, when your legs were tired and you had to negotiate your way down the mountain at the end of the day. Ugh!!! That all changed with the advent of grooming. I have skied so many days, so my knees are victims of a lot of wear and tear, and moguls are not good for them. I still prefer deep powder to any other kind of skiing, but a well-groomed piste of corduroy is also a dream to ski. I adhere to the adage that “If God had intended us to ski moguls, he would have ordained for snow to come down in piles.”

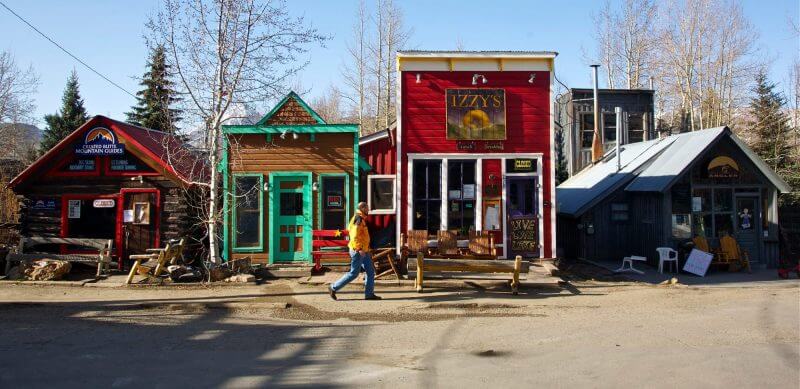

To me, the most negative change is the loss of integrity and authenticity in many ski areas. This has come for a variety of reasons. As ski areas grow larger and larger, the smaller, more cozy and authentic areas no longer can compete, and go out of business. The larger ones overcharge their customers to pay for their growth of course. In addition, many of the US areas use the “real-estate” business model. They buy a small resort, invest in some infrastructure to enlarge the ski area, but primarily build lots of trophy homes, condos, hotels and restaurants. Naturally, they also build a golf course. Their purpose is not really to enhance the ski experience, but rather to increase the value of the property. They sell the houses, and condos, make their profit, and they are satisfied. Whether the ski area itself can sustain itself becomes immaterial. The cute village down the road from the purpose-built resort adjacent to the lifts begins to whither and die. Basically, I do not like purpose-built resorts, which are a kind of generic Disneyland. Give me a real organic ski village every time. I love the village of Crested Butte (below), but do not try to put me into a condo in Crested Butte Mountain Resort. Check me into a small hotel in Jackson. I will make the daily drive to the lifts, but don’t try to place me in Teton Village for a plastic ski-in/ski-out experience.

ITS> This winter will be challenging in the Northern Hemisphere with the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic. How do you think that will affect skiing? Will it end up causing some permanent changes to the ski industry?

Jimmy: I certainly hope not, but it is too early to tell. Unfortunately in the US, you have a few large corporate entities that own and operate many ski resorts. This gives them much too much influence in the industry. The example that they set invariably gets followed by many of the smaller players. As a result, it seems that the main business model for skiing in the US for the 2020-21 season involves a limited number of tickets available and the necessity to pre-buy your ticket online months in advance of the first snow to ensure being able to get on the mountain. While this policy is being touted with the usual B.S. of “Our primary concern is for the health and safety of our beloved customers”, this is certainly as far from the truth as is possible. The correct disclaimer would say, “We are very pleased to have all your money in advance, earning interest. The fact that you must buy a ticket so far in advance that you have no idea whether there will be snow at all, whether the weather will be sunny or rainy or a full-on blizzard is of no concern to us, because we now have YOUR money. If the conditions are poor, the wind is blowing at gale force and/or there is a total white-out, you can be certain that we will keep at least one beginner tow operating so that we do not have to return one dime to our beloved customers.”

By the way, the apparent intention of the Alpine resorts is completely different. They intend to do the best they can in keeping the system the same as usual. They intend to have walk-up ticket sales, no reservations necessary, no limit on customers, masks necessary in lifts and restaurants, and very much hygienic preparation.

ITS> You’ve produced perhaps the most in-depth guide to ski resorts across the globe, in your two-volume set Skiing Around the World. With over 1,000 pages and nearly 1,800 photos, these coffee table books are jam-packed with content that any skier would find captivating, and your first volume was recognized with the prestigious Harold S. Hirsch Award and Bill Berry Award for “outstanding contributions to skiing by the media” given out by the Far West Ski Association. You self-published these books; what was the most challenging part of writing and producing them?

Jimmy> The actual producing of the books has been a joy. Naturally, it has been great fun, adventure, and a marvellous learning experience to travel the world skiing. Secondly, the writing, while time consuming, is creative and fun as well. Thirdly, I have enjoyed working on layout, as that also has its creative aspect. By comparison, editing and proofreading are not much fun—rather tedious and repetitive.

The most challenging part . . . hmmm . . . there are many challenges. The first challenge of self-publishing, is putting up the money and taking the risk with that money. In this case, the cost was about $190,000. As you can understand, that is a lot of money . . . and the reward-risk equation is not a good one. Any smart person would take that amount, invest it in secure corporate bonds or real estate, and watch the money grow without much work or effort. But, naturally, there is more to this project that a “smart financial investment.” These books are a chronicle of my life—they are my contribution to skiing, which has given me so much . . . and it is my wish to share with other like-minded skiers and boarders, in the hopes of inspiring them and adding some joy and adventure to their lives.

Now that the money has been invested, perhaps the other most difficult part is what I do now—trying to organize sales, marketing, and distribution. That is very time-consuming, and I am, unfortunately, a one-man show. With that large investment, there is really no budget for marketing or hiring others to help with this task. With the big hit on the entire ski and travel industry as a result of the corona virus, my timing also turns out to be poor, but I will plug on as best I can. But don’t expect me to work very hard on selling books during the ski season. THAT is devoted to skiing.

ITS>: You’ve already experienced a lot more adventures in life than most people could hope to, but I’m guessing you’re not done yet. What is still on your bucket list?

Jimmy> Another good question . . . To begin with, when I have been working on these books, I rarely had the opportunity to return to a favourite spot, because it was important to gather new material for the book, as well as for articles. Now, with the books finished, I can indulge in some return trips. I would love to revisit some favourite countries like Chile, Iran, and India. I loved skiing in Kashmir (pictured above) and want to return there, for example.

Secondly, there are still a number of countries where I have not skied. I have missed those countries because of considerations of war or terrorism. They include Algeria, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. If I deem it safe enough, I would be happy to still have the opportunity to visit and ski in those countries. Then I have a third idea. As previously stated, I have skied in 649 ski resorts. I would like to reach 1000 . . . or more!!! That might seem difficult, as it has taken me more than 60 years to reach 649, but it is not really that difficult. It merely requires focus on that goal. In the Alps, almost every small village has at least one or two lifts to provide some afternoon entertainment and exercise for the local children. Every one of those villages is therefore, a small ski area. It is easy to ski at least ten of those every day during the winter, taking a few minutes to ski a short T-bar, removing one’s boots, driving to the next village and repeating the procedure. I could reach 1000 in one season, IF I devoted my time to that endeavour.

ITS> What tips would you share with aspiring ski bums who would like to follow in your footsteps?

Jimmy> There are two basic ways of being a ski bum. The one is to get a seasonal job in a ski resort. The other is to save money from your job at home, and live cheaply in the ski resort for the season. The latter is, in my opinion, the better option. Most of the jobs available at ski resorts will not really allow much time for skiing and do not pay well. If you are really going to live your dream and ski a whole season, then do it right, and give yourself the opportunity to really ski every day. Second bit of advice . . . Be careful, ski bumming can become a chronic condition. I am getting close to my 50th season. It is a terminal condition, but I’m not complaining.

ITS> What are some of the ways readers can learn more about your adventures?

Jimmy> As I have written above, I hope some of your readers will buy my books. They are meant to inspire skiers and boarders with ideas and dreams for their own travel and ski adventures. We live on a fascinating planet, and while the best actual ski experiences might be found in the Alps or the Rockies, it is the quest for a mix of skiing with a cultural experience and the desire for adventure that makes a complete vacation. I am certain that my books will help any skier or boarder toward that goal.

All images used by Jimmy Petterson and copyright Jimmy Petterson unless otherwise stated.